Vertical Integration and American Manufacturing Shine at Whelen Engineering

This article was first published in the February 2023 edition of Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment.

By Ed Ballam

For more than 70 years, Whelen Engineering has been an innovator in the warning systems business, manufacturing lights and sirens for everything from large tornado alert systems to lights for fire officers’ SUVs, cruisers, ambulances, and fire trucks. Scene lighting is a huge part of the business as well.

In recent years, Whelen has increasingly become more vertically integrated, able to produce virtually every component of the products it makes as well as even support its own facilities’ physical plant needs with on-staff heating and air-conditioning technicians and truck drivers to move products as needed.

That integration is a source of pride for Whelen and is completely intentional, explains Whelen’s CEO Geoff Marsh.

“We want to control all of the processes at all levels,” Marsh explains. “It’s our way of controlling our own destiny. When we rely on our own processes, we have far better quality control as well.”

Whelen Engineering, founded in 1952, is headquartered in Chester (CT), in a facility that’s about 200,000 square feet. A second, much larger facility is located in Charlestown (NH) on a

40-acre campus with six buildings totaling about 800,000 square feet. As of late fall, the company employed a total of 1,529 people, with about 800 of those located in Charlestown. Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment Editor Ed Ballam was given a VIP tour of that facility in November.

Jerry Maslan, Whelen’s New Hampshire facilities manager, was the tour guide. The Charlestown plant is buzzing with activity on an unseasonably warm early winter day. Maslan points out workers moving dirt for a small drainage project on the campus and says they’re Whelen employees. Shortly after, a 53-foot tractor-trailer truck pulls up the main driveway, emblazoned with a large red Whelen logo on the side of the box. At the wheel is another Whelen employee. Maslan says the company tries to do everything it can in house, part of the vertical integration philosophy that allows the company to be self-reliant and nimble when necessary.

“We have a large facility here, and it doesn’t make sense for us to hire out everything,” Maslan says, noting the company has certified HVAC technicians on board as well as CDL drivers to move goods between Charlestown and Connecticut or wherever they need to go.

“If we need to make a Saturday run, we can without worrying about someone else’s schedule,” he says.

Marsh says vertical integration is a companywide strategy. “We make as much as we can, including all of our subassemblies,” he says, noting the company will only make parts that make sense. For instance, Marsh says Whelen has equipment to make screws, but it’s not part of its core competencies and it is much more efficient to buy that kind of hardware.

Making brackets and other bent metal subassemblies is, however, worth Whelen’s effort, and the company has made significant investments in machines and robotics to produce the components.

Marsh says that having the ability to make those kinds of parts in house means the company can be more responsive to specialty and niche products and customization. Because employees can make the parts themselves, they won’t need to order huge batches of one-off kinds of pieces that would be hugely expensive to order from a third-party vendor.

“We want to earn that business,” Marsh says. “We will work with customers to give them customized experiences.”

For example, Maslan says the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation has a specific order and colored components for warning lights to prevent theft.

“We have the capabilities to do that kind of thing, right in house,” Maslan says.

Marsh says some of the company’s greatest wins have come from the ability to move on customers’ requests quickly. For instance, he says a meeting with the engineering team might happen in the Connecticut office where certain designs and product customization are developed and then, when the clients go to Charlestown for a factory tour, the parts are coming off the line. It’s that kind of service on which Whelen prides itself, Marsh says.

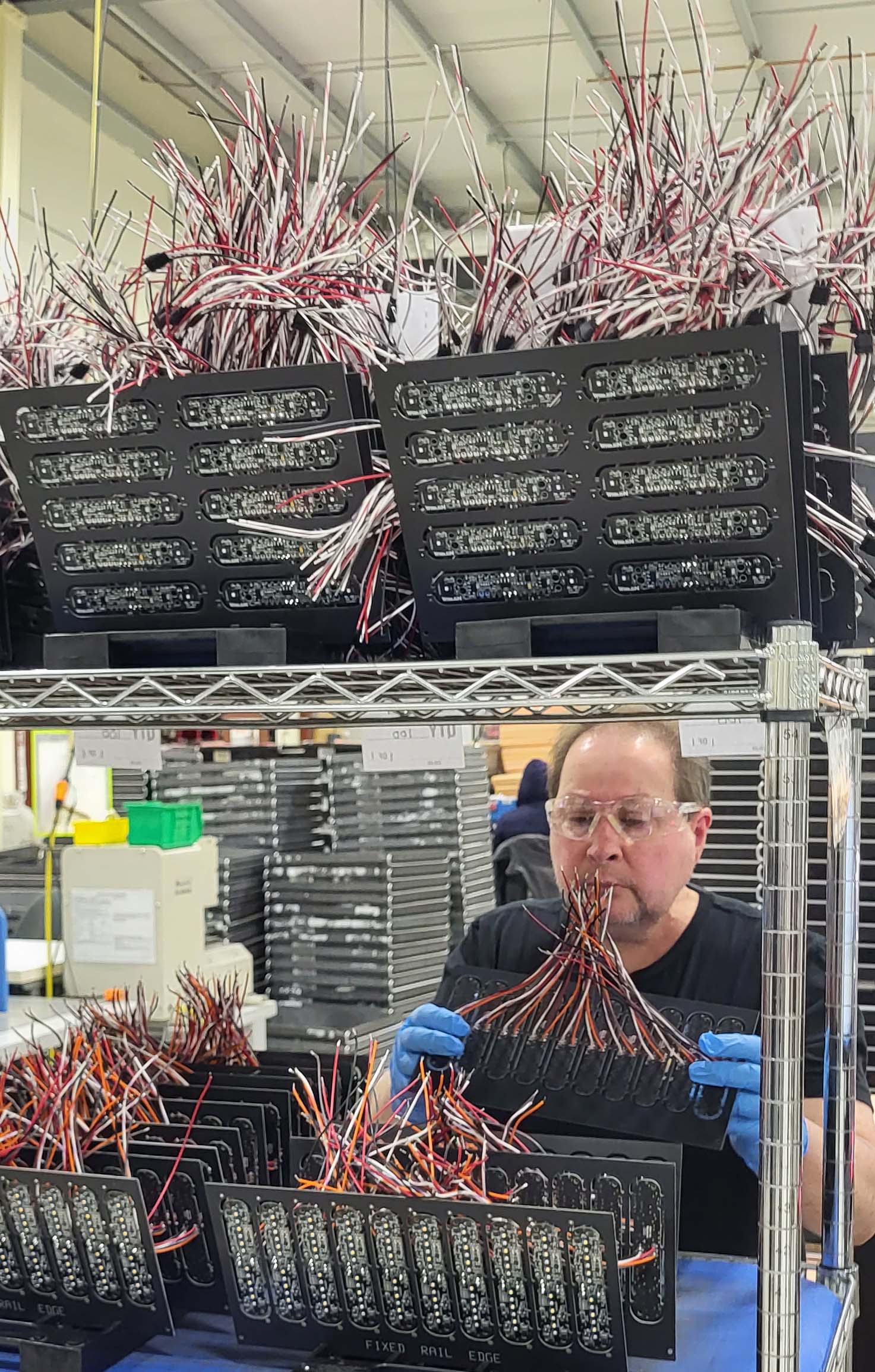

Having that kind of capability has taken a concerted effort to achieve, Marsh says, noting the company has invested heavily in computer aided design equipment, injection modeling equipment, powder coating systems, hard coating equipment, and a myriad of automated and robotic assembly equipment, which frees up their employees to focus on more complicated assembly and production processes.

Marsh says the robotic equipment ensures a high level of quality control in that each assembly is done to exact tolerances with consistency and predictability that is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve with human assembly.

“As we move more toward automation, yes, it reduces human interactions, but it gives us better control and better cycle time,” Marsh says. “We are able to verify quality and fitment. It’s exactly the same every time.” He said if tolerances are faulty, it means parts are wearing out and new tools need to be made and installed, something Whelen can do in house as well.

Marsh adds that people are not designed to do repetitive motions for long periods of time and automation reduces injuries and fatigue on the employees. Whelen places a high value on its workforce and the quality and skills they bring to the products.

“People stay with Whelen a very long time,” Marsh says, adding he wants to make sure the workers are safe and injury free. The average employee has eight years of experience with Whelen, according to human resource records.

Even with automation increasing in Whelen’s plants, Maslan says nearly every piece of every product the company makes is inspected, tested, or checked at least four times for quality control. Checking products to that level means out of approximately 60,000 light bars made by Whelen in the first nine months of 2022, only 10 had issues, Maslan says.

“That’s not bad,” Maslan says, noting that the failure rate is less than .02 percent of production.

Whelen plans to continue the vertical integration and bring more processes in house in the future. In fact, it has created a spinoff company, GreenSource Fabrication, based in Charlestown, to make electronic circuit boards in an environmentally friendly way, says Marsh. He explains the company has developed technology that eliminates heavy metals from entering the wastewater stream through recycling. At the end of the process, there’s a “little brick” of inert material that does not require being handled as hazardous waste.

“It’s an incredible advancement of the technology,” Marsh says.

It’s that commitment to innovation and the embracing of technology that have driven Whelen Engineering, a family-owned company, from the days it was founded by George Whelen in his garage in 1952. He developed a rotating beacon for his airplane and spun the invention into a global business.

“We always want to be ready for the next great idea,” Marsh says. “Innovation can come from anyone, and we want to be ready.”

At Whelen we’re more than just proud of our longstanding history of manufacturing in America. It’s woven into the fabric of who we are as a company, and it’s at the heart of our success. During the pandemic our vertical integration efforts allowed us to avoid many of the supply chain issues that plagued other manufacturers who rely on outsourcing and offshoring for their parts and products.

We can react quickly and make design changes when we face supply chain challenges. Over the past year our engineering team was able to modify and/or redesign over sixty electrical hardware designs including changes to bills of materials, printed circuit board (PCB) schematics and layouts, and embedded code (firmware). Our in-house testing facilities and capabilities ensure there is no compromise on quality and standards.