Debunking Myths About Lumens

This article was first published in the October 2022 edition of Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment.

In October, as the days grow shorter and it gets darker, first responders are increasingly called to emergency scenes with little or no daylight.

This time of year, many of us are thinking about how to increase safety at a nighttime emergency scene and, naturally, “having the best lights” is often at the top of the list. So, what makes one light better than another? Contrary to what you might think, it is not more lumens.

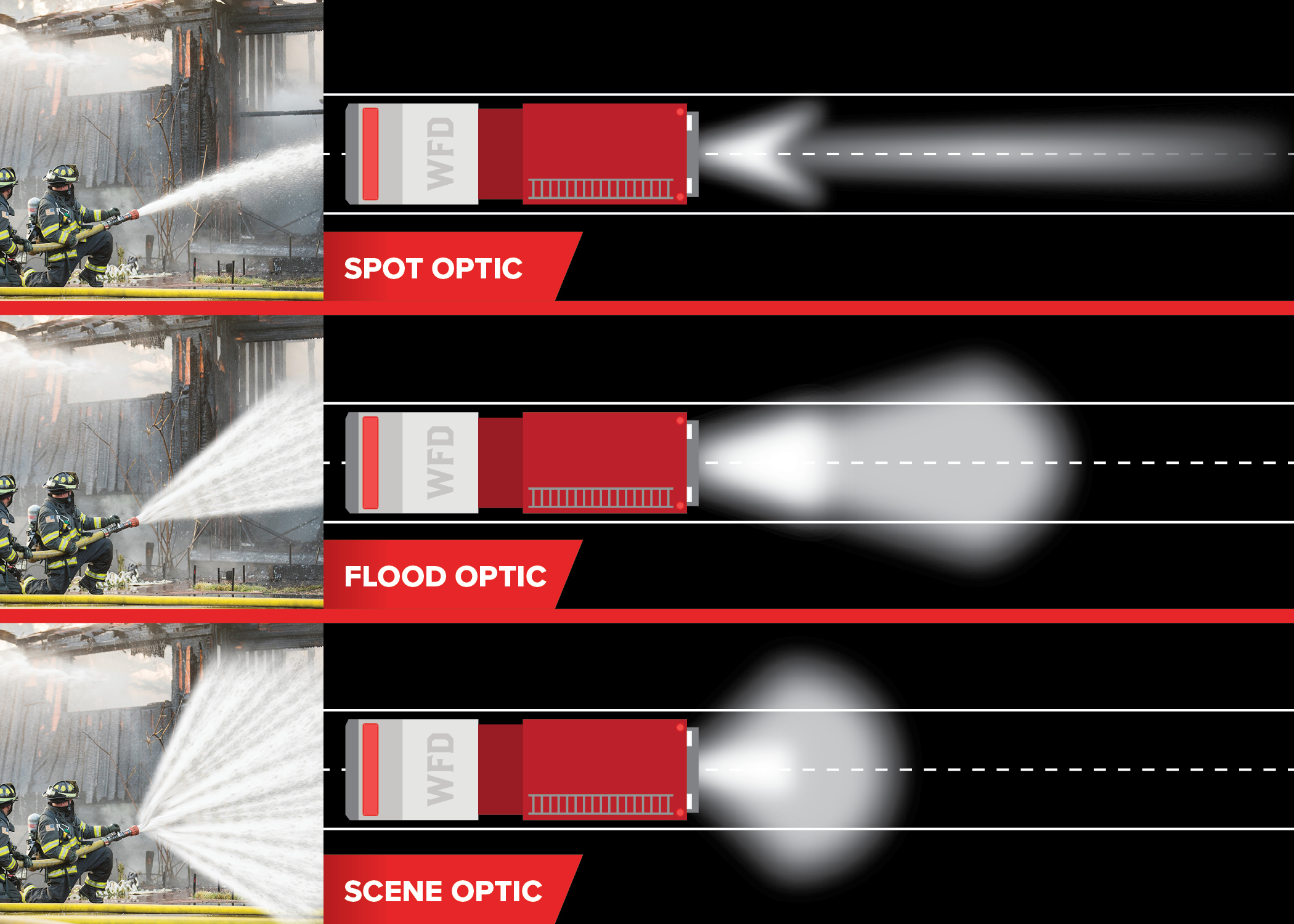

While a lumen is a simple number, easy to reference in marketing materials and manufacturers’ quote-writing programs, lumens don’t tell us the whole story about a light’s performance. One of the best ways I’ve heard someone put lumens into perspective is through the fire hose analogy. Let’s say you have X amount of pounds per square inch (psi) in a water tank pumping system, and you need to spray it through the hose nozzle. In this example, the tank and pump pressure represent lumens, and the nozzle represents a light’s optic. The nozzle spreads the water in a direction through a focused stream or by fanning out, just like the optic focuses a light in a specific direction. Is it narrow? Is it wide? Is it symmetrical or asymmetrical? These are crucial details, which have little or no relationship to psi. Where the water is going and how far it can travel (optics) are just as important as having water pressure (lumens) in the first place (Figure 1).

beam of light.

A fitting example would be Whelen Engineering’s 2-Degree, 8-Degree, and Wide-Flood PAR46 illumination models. All serve different purposes but have the same number of lumens. If the 2-Degree PAR46 had one more diode, it would have a higher lumen rating; however, it would not be the most effective choice if you were trying to flood an area with light.

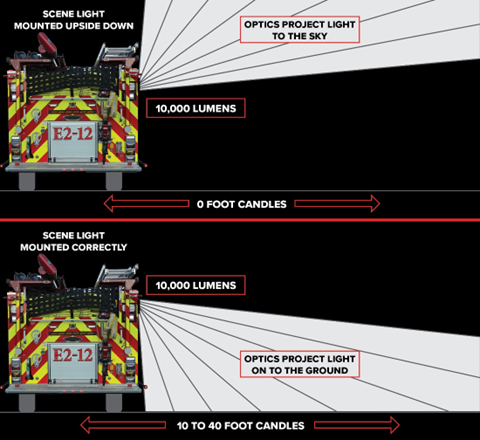

Here is another example to show how lumens don’t correlate with a light’s performance. A typical 10,000-lumen scene light mounted properly on a fire or EMS apparatus optically projects light downward, illuminating a wide area of the ground. The same 10,000- lumen scene light mounted upside down optically projects light upward with little or no light illuminating the ground. So, the same 10,000- lumen number has two very different illumination outcomes because of the different optic design (Figure 2).

depending on the optic design.

Michael Piscitelli, CEO of Sapphire Technical Solutions and vice chairman of the SAE Emergency Warning Lights and Devices Committee, compares the misinformation about lumens in the emergency scene lighting industry with what happened in the flashlight industry.

“Manufacturers would say, ‘I’ve got a flashlight, and it’s umpteen-thousand lumens.’ And then they started using the word candela, and they started saying it’s 500,000 candela and a million candela,” Piscitelli says. “There is no single LED flashlight on the planet that’s putting out a million candela, so many of them were misleading the public by using incorrect units of measure to describe their lights.”

The American National Standards Institute ultimately created two measurements for flashlights. One is Peak Beam Intensity (max candela) and the other is Beam Distance, so you know how big the beam pattern will be at a certain distance. These standards of measurement now allow for an apples-to-apples comparison of flashlights, something that currently doesn’t exist with emergency scene lights.

That’s why Piscitelli recommends our industry follow a similar path and create standards of measurement. “You have to pick a standard to follow because lumens tell you nothing,” he says. “If that light was designed to aim in a direction and now it’s off kilter or turned sideways, the farther you get from the place you’re trying to illuminate, the more it’s going to dim down. You could take a light that’s perfectly good straight down and turn it to a 45-degree angle and it’s going to be significantly less bright by the time it hits the ground,” Piscitelli states.

Confusing the issue even further is all the lumen jargon that now exists, terms like source lumens, raw lumens, usable lumens, effective lumens, etc. And, with no industry standards or guidelines, it’s up to the individual to decide what it all means. For example, some say “raw lumens” isn’t enough to capture the whole story, but one could also argue that “effective lumens” isn’t much better. While “effective lumens” does reflect factors like the amount of light lost as heat, optical diffusion, and efficiencies of the design, it does not consider optics. And, as the fire hose analogy shows, a light’s optic must be considered when factoring its ground illumination effectiveness. In fact, it’s critical, because we know first responders are relying on these lights for their safety as well as the ability to see what they’re doing.

To create the safest nighttime emergency scene possible, you must look deeper than just lumens, regardless of whether you’re talking about effective, usable, equivalent, or raw. Take the time to do your homework and then decide which lights are right for you and your team. A good place to start is to ask the lighting manufacturers to tell you their lights’ total ground illumination values.

In future articles, I’ll delve into the science behind ground illumination and the standards that currently exist and discuss how different optics affect a light’s performance. I’ll also talk about alternative methods for comparing lights, none of which involves lumens.

JIM STOPA worked for 48 years at Whelen Engineering, starting as an electronic technician and climbing the ladder to become an associate electrical engineer, senior electrical engineer, then chief electronic design engineer and electrical department manager, retiring in January 2022. He is credited with 22 patents and is an active participant in many standards groups, such as Society of Automotive Engineers, National Fire Protection Association, Ambulance Manufacturers Division, Fire Apparatus Manufacturers’ Association, and Fire Department Safety Officers Association. Today, he works as a part-time consultant, writes white-paper articles, and speaks at technical conventions, educating the industry about emergency warning technologies.

T